Written specially for the Vikalp Sangam website

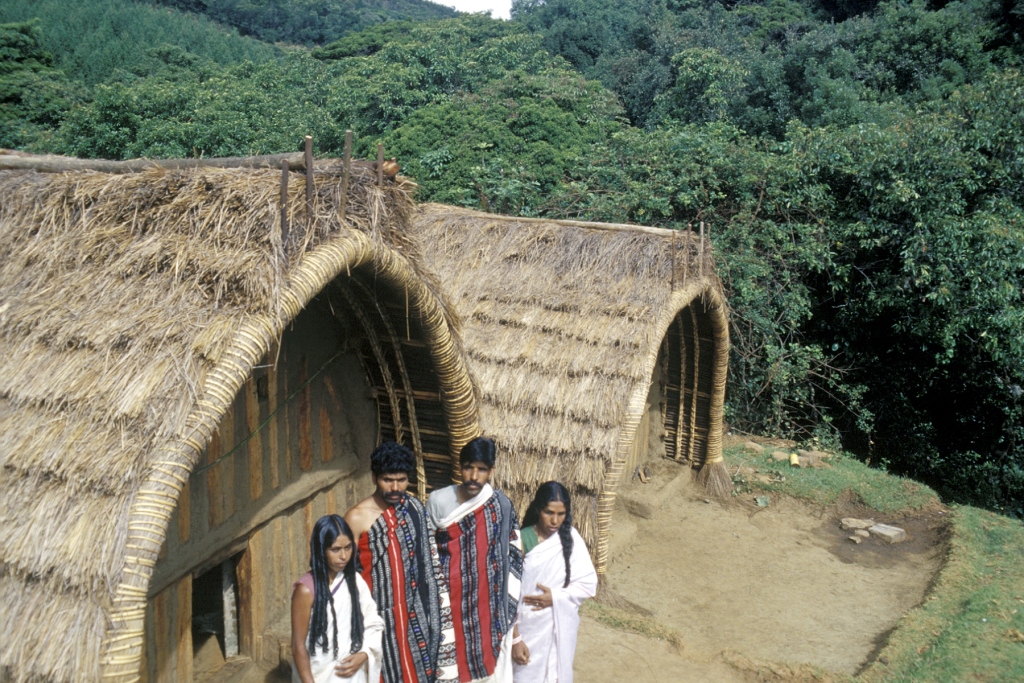

The Toda people are the oldest inhabitants of the Upper Nilgiris plateau of South India and have lived there since ancient times. This, together with their curious barrel-vaulted temples and houses, herds of ferocious long-horned buffaloes, the men’s flowing beards, the women’s distinctive ringlets and both sexes’ embroidered cloaks, has ensured the prominence of this community ever since the Nilgiris were opened up to the outside world two centuries ago.

The Todas’ traditional culture has revolved around their buffalo herds, which are divided into secular and sacred animals. There are six hierarchically-ordered grades of sacred buffalo, whose milk is processed in specially-designated dairy-temples of corresponding grade of sanctity. Only a man who undergoes the elaborate priestly ordination ceremonies that are specific to each grade of dairy-temple and entail the use of a number of thorny plants at a specified water source, may milk the corresponding grade of sacred buffaloes and ritually process it into butter, buttermilk, curd and ghee. The rituals that go into this sacred dairying process are so elaborate that a few tomes would be required to describe the basic processes for each of the different grades of dairy-temples.

At a period when humankind appears to be so disconnected with nature that they assume that their species can survive without respecting other forms of life, it might be pertinent to see how a traditional Toda mind is trained to interact with nature. Not surprisingly, the Toda relationship with surrounding nature begins with their birth rituals. Of course, the neonate is a passive participant, but its mother is required to handle a number of specific plant species to validate the ritual activity. A few weeks thereafter, during the infant’s naming ceremony, a proud grandfather uncovers the child’s face outdoors for the very first time, pointing out to the child various elements of the natural environment: the rising sun, the birds, the buffaloes, bodies of water, and so on. More than likely, the infant will be named after one or another of these surrounding natural phenomena: for a girl, perhaps it will be a flower, a bird’s feather, a precious metal and the like; for a boy, the name might incorporate the sacred name of a specific rock, water course, swamp, hill, shola forest, etc. within the vicinity of the child’s natal hamlet and clan.

Since time immemorial, three irrevocable bonds have linked Todas to their natural environment. In mythic terms, we may say the first of these was established when the Toda gods—deified men and women—chose to reside in certain prominent Nilgiri peaks, ever afterwards furnishing Todas with potent reminders of the unity of nature and divinity. Even today, a Toda elder will consider it sacrilegious to point out the location of a deity hill with his finger. The second great bond with nature is that instituted by their pre-eminent deity, Goddess Taihhki(r)shy, when she miraculously brought forth for the Todas their unique breed of long-horned water buffaloes, dividing the animals into secular and sacred herds. But not only this, the goddess afterwards allocated kwa(r)shm (sacred names) to numerous natural phenomena, amidst which the Todas live. Landscape features constitute the core units of all Toda dairy-temple prayers. These units comprise sacred names of hills, peaks, slopes, shola thickets, paths, trees, pools, streams, swamps, springs, stones, rocks, cliffs, stone circles, buffalo pens, pen posts, pen bars, etc., and are chanted by dairymen-priests in the prayers of nearby hamlets. Consequently, there are rocks that should not be tread upon; plants and waters that are reserved for use only by an ordained dairyman-priest. The Todas’ third indissoluble bond to nature began when Goddess Taihhki(r)shy’s father Aihhn, presiding deity of the Toda afterworld, proclaimed that the only Todas who would qualify to reside, after death, in his realm were those who, during their lifetimes, had diligently performed all the rites of passage required of their gender—rites involving, inter alia, the use of many different kinds of plant material. This means that a Toda requires the use of scores of specified plants to perform their major ceremonies as well as to build their dairy-temples. For example, at the pregnancy rites that occur on the darkness of a new moon night, several species of bamboo reeds, wood and leaves have to be collected from the shola. It is expedient for them to have such species available as close by as possible, rather than to have to trek to some distant forest or meadow. Thus all such plants are conserved and protected. Most sacred ritual activities occur during the dry months when the streams are depleted. Again, it is convenient to recognise and conserve the nearby hydrology conservation species like the endemic Pleiocraterium verticillaris (pollawll ersh in Toda, literally, ‘priests’ leaves’) that holds jugs of water within its vertical rosette of leaves, so that the water sources are perennial.

The Todas also use nature as inspiration for their daily life. Their barrel-vaulted houses and temples are said to have been inspired by the shape of the miniature rainbows that one sees on the highlands, their buffalo pens by the circular pattern of a clump of eihhmehr (Gaultheria fragrantissima) bushes, and even their unique cane milk-churning stick is modelled on the kafehll(zh) (Ceropegia pusilla) flower that has an uncanny resemblance to a miniature churning stick. They also recognise a flower called arkilpoof (Gentiana pedicellata) the ‘worry flower’, which can indicate a person’s anxiety level. If this flower is held by the stem, it closes only if one has worries—faster for more anxious people. And it really works!

Todas traditionally have used plants and flowers to denote not only the season of the year, but also it’s every stage. They can accurately predict the impending end of the southwesterly monsoon by the mass flowering in the sholas of the fragrant white maw(r)sh (Michelia nilagirica) flowers. Similarly, all the different seasons are indicated by the flowering cycles of different plants, certain of them being linked to particular climatic conditions and the position of heavenly bodies. For example, there is a single name for the most prominent star/planet in the night at a particular period, an herb that is in flower at that time and the weather of that season. Toda embroidery patterns are mostly inspired by flowers, butterflies, squirrels, hills, plants, honeycombs, etc., and have now been recognised with the Geographical Indication (G.I.) patent by the Government of India.

Todas not only relate to their flora in cultural terms, but also have a deep knowledge about their utilitarian and botanical roles. For instance, the endemic wetland grass known to Todas as avful (Eriochrysis rangacharii) is the specified thatch to be used for their dairy-temples. The tubers of the terrestrial orchid Satyrium nepalense have been consumed as a potent energiser since ancient times. The Toda name for this plant is ezhtkwehhdr, literally, ‘bullock horns’, because the twin spurs of a plucked flower give the appearance of exactly that. This also tells us that the Todas were aware of the unusual double spurs of this orchid.

The two plant genera that have the most number of endemic species in the Nilgiris are Impatiens and Strobilanthes. The Todas have long taken note of these Nilgiri balsams (Impatiens) and have given the name nawtt.y to the genus. For Todas they are the fourth of the twenty-eight ‘star-weather-plant’ triads that occur during different phases of the year. Certain balsam species also have more specific Toda epithets. For example, the Nilgiri endemic I. rufescens that Todas call tehrrnawtt.y literally, ‘swamp balsam’, is otherwise commonly known as the ‘pink marsh balsam’. When we recently described three new taxa of Impatiens from the upper Nilgiris, they were all given Toda-related names. Impatiens taihmushkulnii was discovered on the slopes of Mount Taihmushkuln, from where the god Aihhn rules over the Toda afterworld; Impatiens kawttyana was located on the slopes of the deity hill Kawtty and Impatiens nilgirica var. nawttyana was named for the Toda epithet for this genus.

The Kurinji plant (Strobilanthes sp.) occasionally flowers en masse in certain areas following the Southwest Monsoon. Several species have been listed, but botanists have only identified the twelve-year cyclic flowering group. The Todas, however, have done better, and know of those that flower at precise intervals of six, twelve and eighteen years. Todas also use the pyoof katt. (eighteen-year flowering Strobilanthes) to determine a person’s age and, therefore, wisdom. Thus, those who had twice witnessed the flowering of the eighteen-year cyclic species since the birth of a family member traditionally knew their relative to be 36 years old.

Most Toda myths mention landmarks that can be seen as actual physical entities in the field, thus giving them an almost magical dimension. The most fascinating of all these stories is that which describes the journey of the departing spirits to Amunawdr, the afterworld. Here, all the over fifteen mythical landmarks that a departing spirit is said to cross on the route to the Toda afterworld, can be seen as actual physical landmarks. For example, at the place where the spirit is said to ascend steps, one can see a stupendous flight of rocky steps that have been hued by nature into an almost vertical cliff face.

The Todas are one of the very few indigenous cultures who chose, several centuries ago, to tread the path of vegetarianism. Undoubtedly, this has added a unique dimension to the manner in which they relate to their natural surroundings. Their pastoral way of life, combined with their non-martial, non-hunting, pacifist, and vegetarian lifestyle has surely played a significant role in ensuring the survival and prospering of the flora and fauna that surround their settlements. Even today, Todas meet with introspection, rather than anger and a desire for revenge, the loss of a buffalo to a predatory tiger residing in the vicinity of their hamlets. Extraordinarily, they are able to accept their loss as being a kind of benediction. The Todas’ intimate link with nature is one of the factors that has endowed the Nilgiris with such a high degree of bio-cultural diversity. It is a fine tribute to this people and to the values they espouse that their sacred homeland in the upper Nilgiris has, in modern times, become the heart of India’s very first biosphere reserve.

It was on the slopes of the deity hills Kawtt.y and Kawnttaihh that the dairyman-priest at the most sacred tee institutions would ritually fire the grasslands to herald the onset of the winter season. This also served an important purpose of direct management of the ecosystem, but has been proscribed by the Forest Department. However, the Todas continue to perform several indirect methods of ecosystem management. The most common and important ritual is that of pouring saline water for the buffaloes at the onset of the different annual seasons by the priest. A failure to perform this ceremony by each of the fifteen extant patriclans is deemed as an invitation for ecosystem ill health, for instance, the failure of the monsoon. Todas also gather annually atop Kawnttaihh deity hill and pray to major hill, water and other sacred sites in the vicinity for ecological and general well-being. Todas still conduct an annual ceremony on top of Paw(r)sh hill, which lies directly above the Pykara River (Kawllykeen), to pray to its presiding deity for blessings and ecosystem health.

Among first societies of the world, the Toda people have been recognised as architects par excellence. Both their barrel-vaulted and conical structures are to be built using only specified forest produce, and can last for well over half a century, requiring only periodic re-thatching (not a single nail goes into these traditional structures). It has even been hypothesised that the Toda conical temples could represent the prototype of the vimana of south Indian temples.

In their spontaneously composed rhythmic lyrics, Toda songs provide us with a well developed art form, which is of great assistance if we wish to comprehend their life patterns, including their relationship to, and interaction with, their natural surroundings. Songs (like the embroidery designs) represent one of the most developed of Toda art forms. Not only are they composed impromptu and sung in a unique manner, Toda songs constitute a tightly-bound poetic form, with relatively rigid rules and parameters. Verses are split into units of fixed length—in most cases, of three syllables, but occasionally ranging from two to five syllables. Their spontaneously composed songs are a unique form of oral poetry that has been described as a combination of Homeric, Hebrew poetry with its parallelism of phrases, and the use of a stereotyped corpus from the Vedas.

From the early days after arrival of the British, an enduring romantic fascination for the Todas with their quaint culture, striking countenance and magically beautiful landscapes, began to unfold for their newfound colonial masters. Moreover, they had met their match in an aboriginal group that showed absolutely no sense of servitude. Indeed, the Todas appeared to look upon Western culture with distinct condescension. John Sullivan, the founder of modern Ooty, himself notes that: ‘It was [only] for the second time that they saw white men, but I was perplexed by their majestically calm attitude; it resembled so little the slavish manners of the natives in India whom we were accustomed to see. They seemed to await our arrival …’

The Toda people were experiencing the pure joys of nature-centric life when the British entered their homeland. They were in total tune with nature whilst living in an seemingly endless and beautiful landscape that was sacred to them, without the hindrances and encumbrances of personal ownership, all families owned similar looking dwellings that could be erected in a few days, without stirring any feelings of jealousy; food and possessions were collected from the vicinity or exchanged with other indigenous groups. Every Toda had access to basic food, shelter and clothing, besides being part of an extended family—his clan, division and community. Thus, the concept of orphans and old age destitution did not exist. Toda society worked along prescribed societal rules and customs of mutuality. In fact, until as recently as half a century ago, the concept of locking their dwellings was almost unknown.

Although the Todas remain a demographically small endogamous group—at just over fourteen hundred orthodox members—the manner in which they have organised their society has worked well for them. In India, many small ethnic communities, with populations even exceeding a hundred thousand, are experiencing genetic problems due to their endogamous marital culture. The Todas on the other hand, seem to be quite free from the genetic defects of inbreeding.

Contact the author

Readers wanting to know more about Toda culture can read the author’s book: The Toda Landscape: Explorations in Cultural Ecology (Orient Black Swan and Harvard University Press, Harvard Oriental Series, vol.79; 2015)